The sheer pleasure of driving a Scalextric car cannot be overestimated…

There’s nothing better than hearing the shrieks of joy as a young child presses that trigger for the first time and sees their car whizz round the track. Once you’ve caught the Scalextric bug, you tend to keep it for the rest of your life.

Most laps clocked up by the average Scalextric car won’t be part of a competitive race or even a timed practice session. Many will be ‘solo’ laps or driving against another car just for fun. There are Scalextric sets designed for cruising your hypercars or for cops ‘n’ robbers-style car chases – and there is now the fabulous Spark Plug which has turned up the fun-factor to maximum.

However, for the entire history of Scalextric, the main focus of the product range has been motor sport and racing.

There are plenty of different ways to race – most of them based on real motor racing

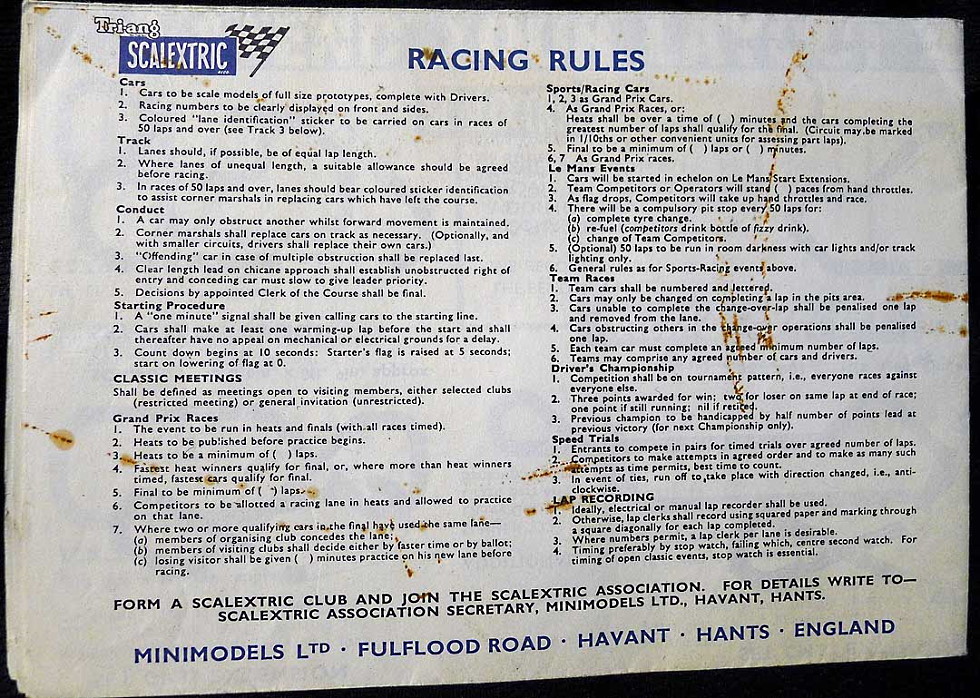

If you like Formula One, British Touring Cars, Goodwood Revival, the Le Mans 24 hours, rallying or even drag racing, you can replicate it with Scalextric. The basic principles for race formats go back over sixty years, even before the birth of Scalextric. The ‘Racing Rules’ from the back page of the first ever Scalextric catalogue came from the model car racing clubs of the time – and are rather dictatorial. They did get toned down quite a bit in the next catalogue.

The key piece of equipment you need for racing is a way of counting laps

That can be done manually by simply making marks on a piece of paper or – more usually – by using an automatic lap counter. Some of the Scalextric starter sets include a mechanical lap counter that will record up to fifty laps for each lane – and then start from zero again. For many years, a mechanical lap counter was all Scalextric racers had – it is quite sufficient, especially when used with a stop watch.

Over the past thirty years, more complex lap counters have been produced, which also time the race and individual laps. The pinnacle of this development process is the ARC app and the ARC One, ARC Air and ARC Pro powerbases. Lap counting and timing are only a small part of the ARC system, but they are probably the most important features.

We will base our racing guidelines on the ‘General Racing Notes’ from the 1961 Scalextric catalogue – they have certainly stood the test of time…

General – to apply to all racing formats

1. One specific class of car can be chosen – for example, Formula One, BTCC, Rally, GT3, Historic or Le

Mans Prototype – or a mix of cars can be used in ‘Formula Libre’ style racing.

2. The choice of lane shall be decided by the toss a coin or drawing lots.

3. Corner marshals will be appointed to replace cars if they crash. Alternative format: competitors replace

their own cars.

4. A car may only obstruct an opponent while forward movement is maintained.

5. Where an obstruction is caused by a car stopping on the track, the obstructing car shall be replaced

after the innocent car.

6. The winner shall be the first car to complete the agreed race distance.

7. The judge’s decision is final.

Race Formats

1. Lap Races: the race lasts for an agreed number of laps. Examples – Formula One, BTCC etc.

2. Endurance Races: the race runs for an agreed length of time, competitors completing as many laps as possible. Examples – Le Mans, British GT Championship, American IMSA etc.

3. Time Trials: Cars are timed individually over an agreed number of laps, the winner completing those

laps in the quickest time. Examples – Rally, sprint race, drag race, Targa Florio etc.

Team Races

1. The race may use a Lap, Endurance or Time Trial format.

2. Teams made up of two, three or four drivers, each racing the car for a set number of laps or period of

time before handing over to the next team member.

3. At driver changes, the car must be stationary and must not obstruct the other cars. Ideally, the cars

should stop in an agreed ‘pit area’.

4. Each team member must race for an agreed minimum amount of time.

Tournament Racing

1. Any number of racers can take part. Every competitor races against everyone else.

2. Racers are entered into a table to see who they have raced and the result of each race.

3. Race winners are awarded 3 points, the loser is awarded 2 points if they finish on the same lap, 1 point if they are a lap or more behind – and no points if their car retires (for digital races and circuit with more than two lanes, the point system can be adjusted).

If you look at the ARC app, the basic formats are not dissimilar to sixty years ago! However, technological developments mean today’s Scalextric racers can add far more detail and realism to their racing. For example, if you have lap timing, then proper qualifying sessions and extra points for fastest laps are possible.

One thing that the 1960s guidelines fail to consider is that one lane of an analogue track is often ‘better’ than the other. Unless you build a track with a flyover, one lane will always have a slight advantage. The easiest way around this is to accept it – if you win from the ‘worst’ lane then your victory is even sweeter. Alternatively, you could each race on both lanes and add together the race times (or laps for a timed race) – the winner is the racer who has the quickest combined race time (or completed the most laps in the same time). You could also keep the same car on each lane when you swap – that is a true test of who’s best.

Of course, the racing is only part of the story. Decorating the room, presenting prizes and sharing pictures, video and results on social media all make the event even more enjoyable and memorable. This is just a quick introduction to race formats and rules. Look out for more race format blog posts.